Lyrical dramatization. Floating stanzas in McDowell’s early recordings (1959-1967)

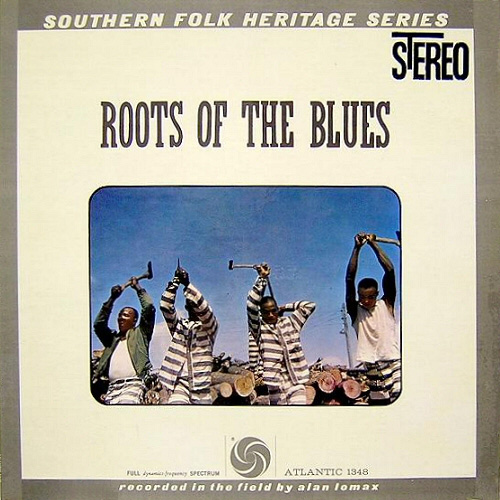

The collection of Fred McDowell’s amazing pieces generally called his “early recordings[1]” mixes various lyrics which are not easily untangled – and may even be confusing for the one who tries to learn them (if they may be “learned”). Everything must be considered from the bottom, or his seminal songbook, for example from the song entitled Freight Train Blues, recorded by Alan Lomax with the assistance of Shirley Collins at McDowell’s home in Como on September 21 1959, during a famous session of field recordings. Freight Train Blues appeared on the second album which allowed to discover Lomax’s recordings: Roots Of The Blues, that followed Sounds Of The South in the collection Southern Folk Heritage Series – both published by Atlantic in 1960.

Sounds Of The South was published in 1960, with a booklet, in U.S. in mono and stereo (Atlantic SD-1346) and in U.K. (London LTZ-K 15211), with a new release in U.S. on Atlantic in 1968 (Atlantic SD-1346) and another one on Polydor-Atlantic in U. K. (590 033). At that time, British blues leaders – among them, the Rolling Stones and Keith Richards – had fully discovered McDowell amazing talent. And it was again highlighted in the four cds boxset entitled Sounds Of The South, published by Atlantic in 1993 (782496). McDowell was notably heard on the second volume, which had not Freight Train Blues.

Source: https://www.wirz.de/music/mcdowell.htm

Source: https://www.wirz.de/music/mcdowell.htm

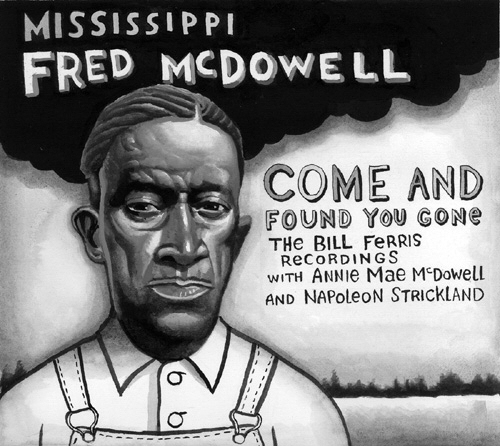

The closest relationship between Freight Train Blues and another McDowell’ song seems to be provided by Letter From Hot Spring, which was recorded by Bill Ferris on August 1967 and only published in 2010 on Devil Down Records. The 33 vinyl included McDowell, his wife Annie Mae McDowell on vocals, Napoleon Strickland on harp and an unidentified musician on vocals. The notes are due to Bill Ferris, Luther Dickinson and Vincent Joos.

We put in colours the corresponding stanzas. Fred introduce the song, in Ferris’ version, by: “I got a song… Am I wrong… I Got a Letter From Hot Spring… You must have heard that”. He could refer to Freight Train Blues.

| Freight Train Blues Recorded by Alan Lomax (1959) Played in open D major Transcription by Bendude |

Letter From Hot Spring Recorded by Bill Ferris (1967) Played in open E-Flat major Our Transcription |

| I got on that freight train; I tried to beat my way. Lord, them rocks and gravel, Lord, flew all in my face. |

Oh I got a letter from Hot Spring Tell you how it was read. Lord, it’s come at once, boy: your sure-‘nough gal is dead. |

| I (?) conductor, let me ride it blind. Lord, he shook his head, said, “The train ain’t none of mine.” |

I got on a freight train, and I, I tried to beat my way. Well, them rocks and gravel, Flew all in my face. |

| I got a letter from Hot Spring. I tell you how it was read. Lord, it’s come at once, boy: your sure-‘nough gal is dead. |

Lord ? conductor Please let me ride this blind. Well he shook his head, “You know the train ain’t none of mine.” |

| Said I left my baby Standin’ out back door cryin’. I never felt so sorry, Lord, till she said goodbye. |

Theme ((Fade away)) |

Did McDowell refer to another song than Freight Train Blues when he was announcing Letter From Hot Spring? We have to search for this in the intermediary “early recordings”, that is to say those made by Dick Spottswood on April 21/22 1962 at McDowell’s home in Como. They only be released on the album Mississippi Fred McDowell 1962. His First Recordings Following Discovery, published in U. K. on Heritage with notes by Chris Smith (Heritage HT 302). It will be reedited in 1989 on Flyright with notes by Bruce Bastin (Flyright FLY CD 14) and afterwards in 1995 on Rounder with notes by Tom Pomposello (Rounder CD 2138).

https://www.wirz.de/music/mcdowell.htm

https://www.wirz.de/music/mcdowell.htm

Among these recordings, the typical melodical frame used in Freight Train Blues – we could say: the fundamental structure of McDowell’s open tuning rhythm/slide music – is used in the two first songs, Done Left Here and All The Way From East St. Louis, whose illustrate their eminent place in McDowell repertoire. But a song, Left My Baby Standing, directly appeals to Freight Train Blues and Letter from Hot Spring, by this structure and by the lyrics, so that we have to compare the three songs.

| Freight Train Blues Alan Lomax recording (1959) Played in open D major Transcription by Bendude |

Left My Baby Standing Dick Spottswood recording (1962) Played in open D major Our transcription |

Letter From Hot Spring Recorded by Bill Ferris (1967) Played in open E-Flat major Our Transcription |

| I got on that freight train; I tried to beat my way. Lord, them rocks and gravel, Lord, flew all in my face. |

Said, I left my baby standing In our back door cryin’ Never felt so sorry no Till she said goodbye. |

Oh I got a letter from Hot Spring Tell you how it was read. Lord, it’s come at once, boy: Your sure-‘nough gal is dead. |

| I asked the conductor, Let me ride it blind. Lord, he shook his head, said, “The train ain’t none of mine.” |

I’m goin’ by the pawn shop, Put my watch in pawn. I don’t nobody tell me How long my baby been gone. |

I got on a freight train, and I, I tried to beat my way. Well, them rocks and gravel, Flew all in my face. |

| I got a letter from Hot Spring. I tell you how it was read. Lord, it’s come at once, boy: Your sure-‘nough gal is dead. |

What you gonna do When your trouble get like mine? ? ? |

Lord ? conductor Please let me ride this blind. Well he shook his head, “You know the train ain’t none of mine.” |

| Said I left my baby Standin’ out back door cryin’. I never felt so sorry, Lord, till she said goodbye. |

I got a letter from Hot Spring, I tell you how it was read Lord, it’s come at once, boy: Your sure-‘nough gal is dead. |

Theme ((Fade away)) |

| I got on that freight train; I tried to beat my way. Lord, them rocks and gravel, Flew all in my face. |

||

| I asked the conductor, Let me ride it blind. Lord, he shook his head, said, “The train ain’t none of mine.” |

The remaining question about Left My Baby Standing is: from where are coming the second and third stanzas? They are also borrowed from the Lomax recordings. See below:

| You’re Gonna Be Sorry Alan Lomax recording (1959) Our transcription |

Left My Baby Standing Dick Spottswood recording (1962) Played in open D major Our transcription |

| Lord, you’re gonna be sorry Ever done me wrong, I don’t beat you lady, Honey, and I’ll be gone. |

Said, I left my baby standing In our back door cryin’ Never felt so sorry no Till she said goodbye. |

| I’m goin’ by the pawn shop Put my watch in pawn. (slide) |

I’m goin’ by the pawn shop, Put my watch in pawn. I don’t nobody tell me How long my baby been gone |

| What you goin’ do, baby When your trouble get like mine? Lord, you can’t do me Honey, like you did wit’ done, Po’ Shine Lord, you took his money, babe But swear you can’t take mine |

What you gonna do When your trouble get like mine? ? ? |

| Lord, I wonder What’s the matter now? Lord, I wonder What’s the matter now? Lord, I wonder What’s the matter now? (slide) |

I got a letter from Hot Spring, I tell you how it was read Lord, it’s come at once, boy: Your sure-‘nough gal is dead. |

| Lord, I ‘m still wonderin’ Don’t know to do Lord, I ‘m still wonder, baby What gonna ‘come of me? Well, just come on, baby Take a little walk wit’ m |

I got on that freight train; I tried to beat my way. Lord, them rocks and gravel, Flew all in my face. |

| I asked the conductor, Let me ride it blind. Lord, he shook his head, said, “The train ain’t none of mine.” |

It is clear now that Left My Baby Standing used various stanzas from Freight Train Blues and You’re Gonna Be Sorry, as if McDowell was searching for a new and different song, on a different musical structure. It is also striking that You’re Gonna Be Sorry, played with Mile Pratcher on guitar, is not sung on the typical melodical frame mentioned above and that the lyrics are also organized in a different way, with many repeated and not very clearly separated verses. In fact, we have the impression that McDowell was more or less improvising or experimenting a not yet well mastered song.

It is also striking that You’re Gonna Be Sorry and Left My Baby Standing develop the topic of “broken love”: “Lord, you’re gonna be sorry /Ever done me wrong” or “Never felt so sorry no /Till she said goodbye”. But Freight Train, in contrast, moved a different – and deeper – emotional feeling as it was telling about the death of the “sure-‘nough gal”. McDowell got back to this more dramatic register or tone, which was also more “original” as Freight Train lines were directly and first adapted to his musical uniqueness. Moving from lyrical or elegiac tone to the tragic, he was the joining the tradition illustrated by Son House’s Death Letter Blues or Blind Willie McTell’s Death Room Blues (rather than Cooling Board Blues, oddly played in ragtime).

See Blues Maker, Univ Of Mississippi, 1969

Shows Mississippi blues singer, Fred Mc Dowell, singing and talking about his blues. Includes scenes of the area which helped to shape his country blues.

Joseph Brems, Muriel Collart, Daniel Droixhe (aka Elmore D.), Gilles Droixhe

[1] The Penguin Guide to Blues Recordings, ed. by Tony Russell and Chris Smith with Neil Slaven, Ricky Russell and Joe Faulkner, Penguin Books, 2006, “Fred McDowell”, p. 641-643.